Thomas Becket and the Struggle Between Crown and Church

This week in History: 29 December 1170: The Murder of Thomas Becket

In A Symphony of Echoes by Jodi Taylor, the team from St Mary’s Institute of Historical Research jump into the volatile world of twelfth-century Canterbury and bear witness to the moment when political fury erupts into violence with the murder of Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury.

On 29th December 1170, one of the most shocking acts of violence in medieval European history took place within the walls of Canterbury Cathedral. Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury and the most senior churchman in England, was cut down by four knights while attending to his ecclesiastical duties. The killing reverberated far beyond England, reshaping relations between church and crown for generations and leaving a permanent mark on medieval political thought.

Becket was not born a rebel. The son of a prosperous London landowner, he rose through ability and royal favour to become Chancellor of England under King Henry the Second. In this role, he was loyal, efficient and worldly, vigorously defending royal interests and living in a manner befitting a powerful courtier. When Henry secured Becket’s appointment as Archbishop of Canterbury in 1162, he expected a trusted ally who would support his efforts to bring the English church more firmly under royal control.

The transformation that followed surprised and infuriated the king. Becket embraced his new role with uncompromising seriousness, adopting an austere lifestyle and defending the autonomy of the church with unexpected ferocity. The central issue was jurisdiction. Henry sought to limit the privileges of the clergy, particularly the right of church courts to try clerics accused of serious crimes. Becket resisted, arguing that ecclesiastical independence was divinely sanctioned and essential to the moral authority of the church.

The dispute reached a crisis with the Constitutions of Clarendon in 1164, a set of royal customs intended to define the limits of papal and ecclesiastical authority in England. Becket initially appeared to accept them, then withdrew his consent, claiming his conscience would not allow it. The breach with Henry widened into open hostility. Accused of financial impropriety and contempt of royal authority, Becket fled into exile in France, where he remained for six years.

During this period, the conflict acquired a wider European dimension. Becket appealed to Pope Alexander III, while Henry sought to assert English independence from papal interference. Both sides used the tools of spiritual and temporal power, including threats of excommunication and political pressure, in a struggle that symbolised the broader tension between secular rulers and the medieval church.

A fragile reconciliation allowed Becket to return to England in 1170. It proved short-lived. His continued defiance, including the excommunication of bishops loyal to the king, provoked renewed anger at court. According to later chroniclers, Henry uttered words of frustrated rage, lamenting that no one would rid him of this troublesome priest. Four knights interpreted this as a call to action.

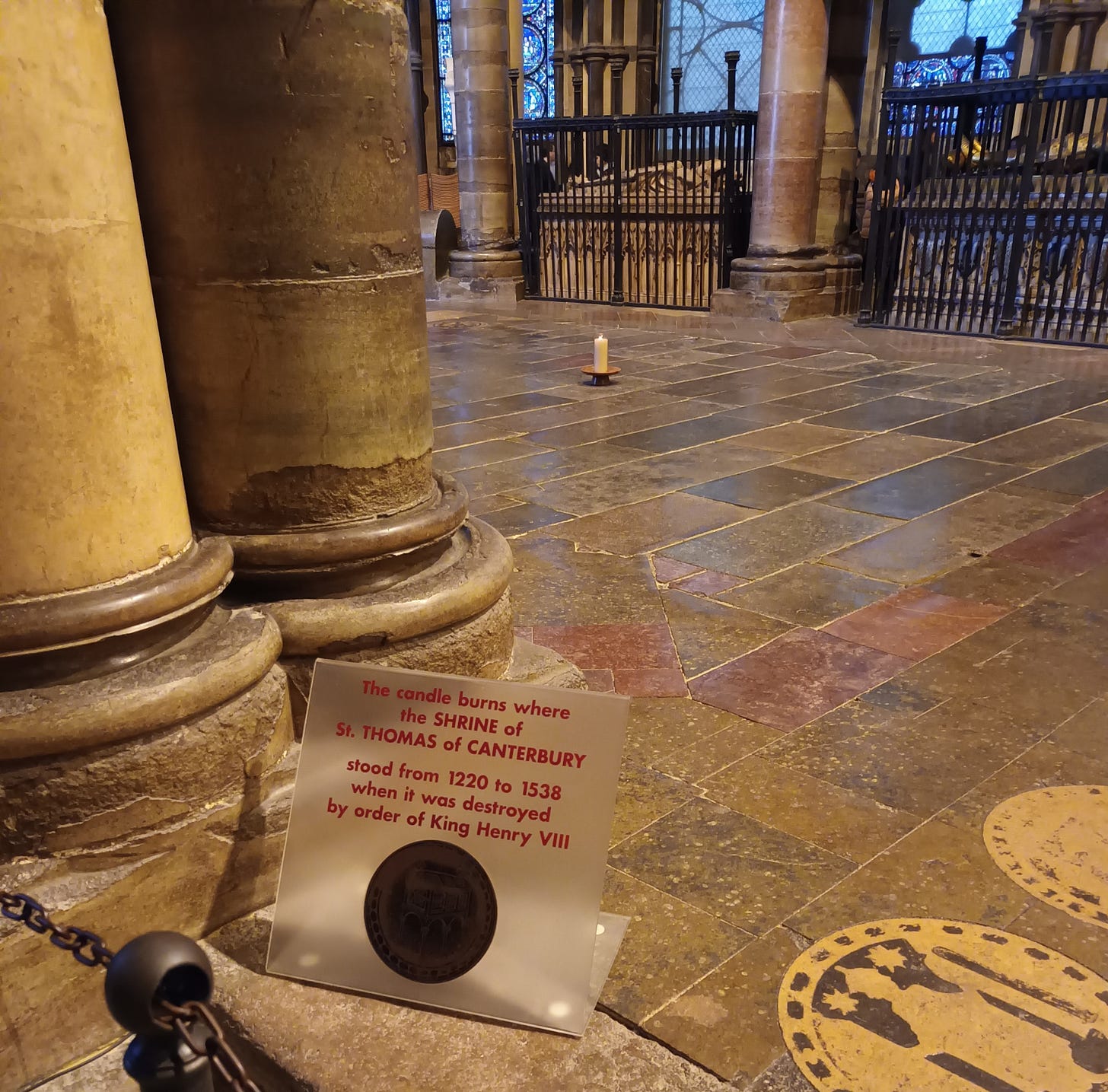

They travelled to Canterbury and confronted Becket in the cathedral. Despite opportunities to flee or seek sanctuary, Becket refused. He was struck down near the altar, his blood spilled on consecrated stone. The brutality of the act, carried out in a sacred space, shocked contemporaries and transformed Becket from a controversial figure into a martyr almost overnight.

The reaction was swift and severe. Becket’s tomb became a site of pilgrimage, and reports of miracles spread rapidly across Europe. Within three years he was canonised as Saint Thomas of Canterbury. Henry the Second, facing outrage at home and abroad, was forced into public penance. In 1174 he walked barefoot to Canterbury and submitted to ritual scourging at Becket’s shrine, a powerful image of royal humiliation before spiritual authority.

Politically, the murder strengthened the position of the church in England and beyond. It demonstrated the risks faced by rulers who challenged ecclesiastical independence too openly. While Henry retained significant influence over the English church, his ambitions were tempered, and the principle that the church possessed rights beyond royal command was reaffirmed.

Nearly nine hundred years later, the site of the murder still draws visitors, not only as a place of worship, but as a reminder of the enduring struggle between conscience and power, and of the moment when bloodshed in a cathedral altered the course of church-state relations in medieval Europe.

To discover how Max and the St Mary’s team survive the dangers of twelfth century Canterbury, and how close they come to events that still echo through English history, readers can turn to A Symphony of Echoes by Jodi Taylor, available in paperback, ebook and audiobook editions.

I hope you have enjoyed this foray into history. Please subscribe to read more articles like this one. CLICK HERE to read more History Briefings.

Have you discovered The Official Reading Companion and History Briefings for The Chronicles of St Mary’s series by Jodi Taylor?

If you've ever found yourself wondering who did what, when, and where in Jodi Taylor’s brilliant Chronicles of St Mary’s series — this is the companion guide you’ve been waiting for.

This guide is a must-have for both dedicated fans and curious newcomers. It contains synopses of every book and short story, detailed floor plans of St Mary’s Institute for Historical Research, History Briefings, chronological jump lists, character information, and more.

Whether you’re brushing up on the timeline or want to immerse yourself further in the chaos and charm of St Mary’s, this guide is your ultimate companion.

CLICK HERE to learn more.