Innovative Architectural Elements in the Rebuilding of St Paul’s Cathedral

This Week In History: The Official Opening of St Paul’s Cathedral 2 December 1697

The formal opening of St Paul’s Cathedral on 2 December 1697 marked the culmination of one of the most ambitious architectural and ecclesiastical reconstruction projects in early modern Europe. The reconstruction after the Great Fire of London placed Christopher Wren at the forefront of architectural experimentation in late seventeenth-century England. Wren’s design was not merely a restoration of the medieval fabric but a boldly conceived reinvention, integrating classical forms, empirical engineering, and Baroque dramatic effect on a scale previously unseen in England. The resulting structure became a landmark of European architecture and a symbol of the emerging scientific and artistic confidence of the period.

One of the most striking innovations was Wren’s use of a triple-dome construction, a sophisticated engineering solution that allowed him to reconcile competing aesthetic and structural demands. The outer dome, visible from the London skyline, achieved the monumental silhouette Wren desired. Beneath it, a concealed brick cone provided the true structural support, transferring the immense weight safely downward. A third dome formed the interior surface seen from the nave, lower and more harmonious with the internal proportions. This tripartite system was unprecedented in England and demonstrated Wren’s close engagement with continental engineering, particularly that of François Mansart and the Italian Baroque, while adapting it to local materials and tectonic needs.

Equally significant was Wren’s structural use of Portland stone in vast quantities and with extraordinary precision. The uniform grey limestone allowed for crisp classical detail and proved resilient in London’s polluted atmosphere. Wren exploited this material to create a coherent classical language across the building, from pilasters and entablatures to the great west front with its twin towers. These towers themselves illustrate Wren’s willingness to innovate: originally conceived as simple campaniles, they evolved into richly modelled Baroque compositions during construction, integrating curves, projecting cornices, and sculptural decoration. Their dynamic form contrasted sharply with the Gothic verticality of England’s medieval ecclesiastical architecture.

Wren also introduced advanced techniques in load distribution and fireproofing. The extensive use of brick vaulting, masked by stone ribs and plaster, significantly reduced the risk of fire and improved structural stability. This decision reflected lessons learned from the catastrophic destruction of 1666. Moreover, iron chains embedded within the masonry acted as tension rings at strategic points beneath the dome, countering lateral thrust and preventing deformation. These discreet reinforcements represented an early use of metal in large-scale structural systems and demonstrated Wren’s scientific approach to architectural problem-solving.

The cathedral’s interior innovations were equally noteworthy. Wren employed an entirely classical spatial arrangement, replacing the medieval reliance on pointed arches and rib vaults with a rhythmic procession of pilasters and round arches inspired by Roman basilicas. He carefully calculated the proportions to produce an interior space that combined grandeur with clarity. The choir and nave were unified under a continuous entablature, creating an unbroken visual flow. Natural light was manipulated with great sophistication: concealed windows and the lantern above the dome illuminated the crossing, while clerestory openings emphasised the articulation of the nave. Such attention to controlled luminosity echoed continental Baroque design but retained a distinctly English restraint.

The cathedral’s decorative programme also reflected Wren’s innovative spirit. Rather than replicating the densely carved surfaces typical of continental Baroque interiors, Wren opted for a more austere aesthetic, relying on geometry, proportion, and the play of light across smooth surfaces. Later additions, including Sir James Thornhill’s dome paintings, were carefully integrated into Wren’s scheme without compromising its architectural discipline.

I hope you have enjoyed this foray into history. Please subscribe to read more articles like this.

CLICK HERE to read more History and Happenings articles.

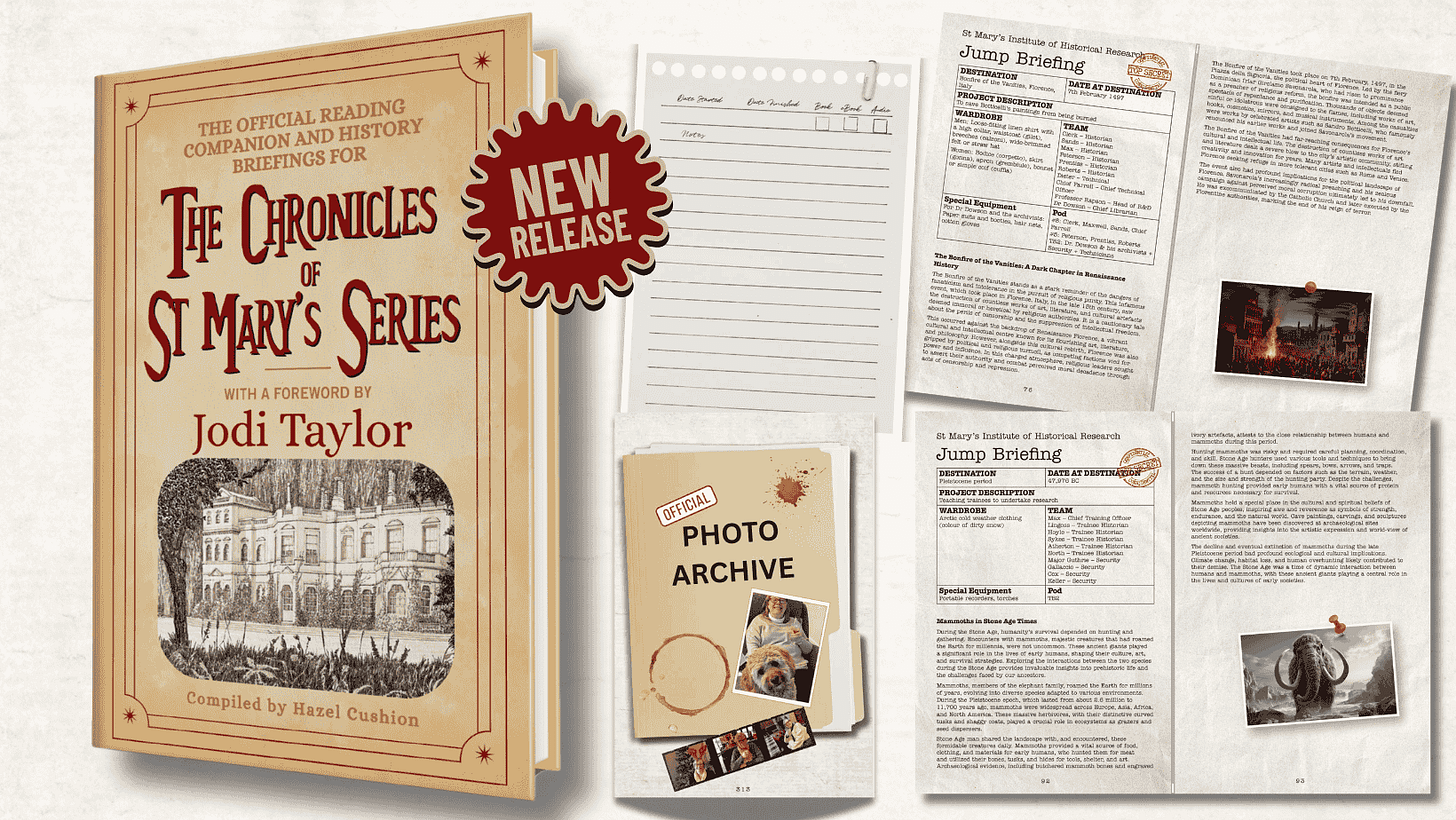

Have you discovered The Official Reading Companion and History Briefings for The Chronicles of St Mary’s series by Jodi Taylor?

If you’ve ever found yourself wondering who did what, when, and where in Jodi Taylor’s brilliant Chronicles of St Mary’s series — this is the companion guide you’ve been waiting for.

This guide is a must-have for both dedicated fans and curious newcomers. It contains synopses of every book and short story, detailed floor plans of St Mary’s Institute for Historical Research, History Briefings, chronological jump lists, character information, and more.

Whether you’re brushing up on the timeline or want to immerse yourself further in the chaos and charm of St Mary’s, this guide is your ultimate companion.

CLICK HERE to learn more.