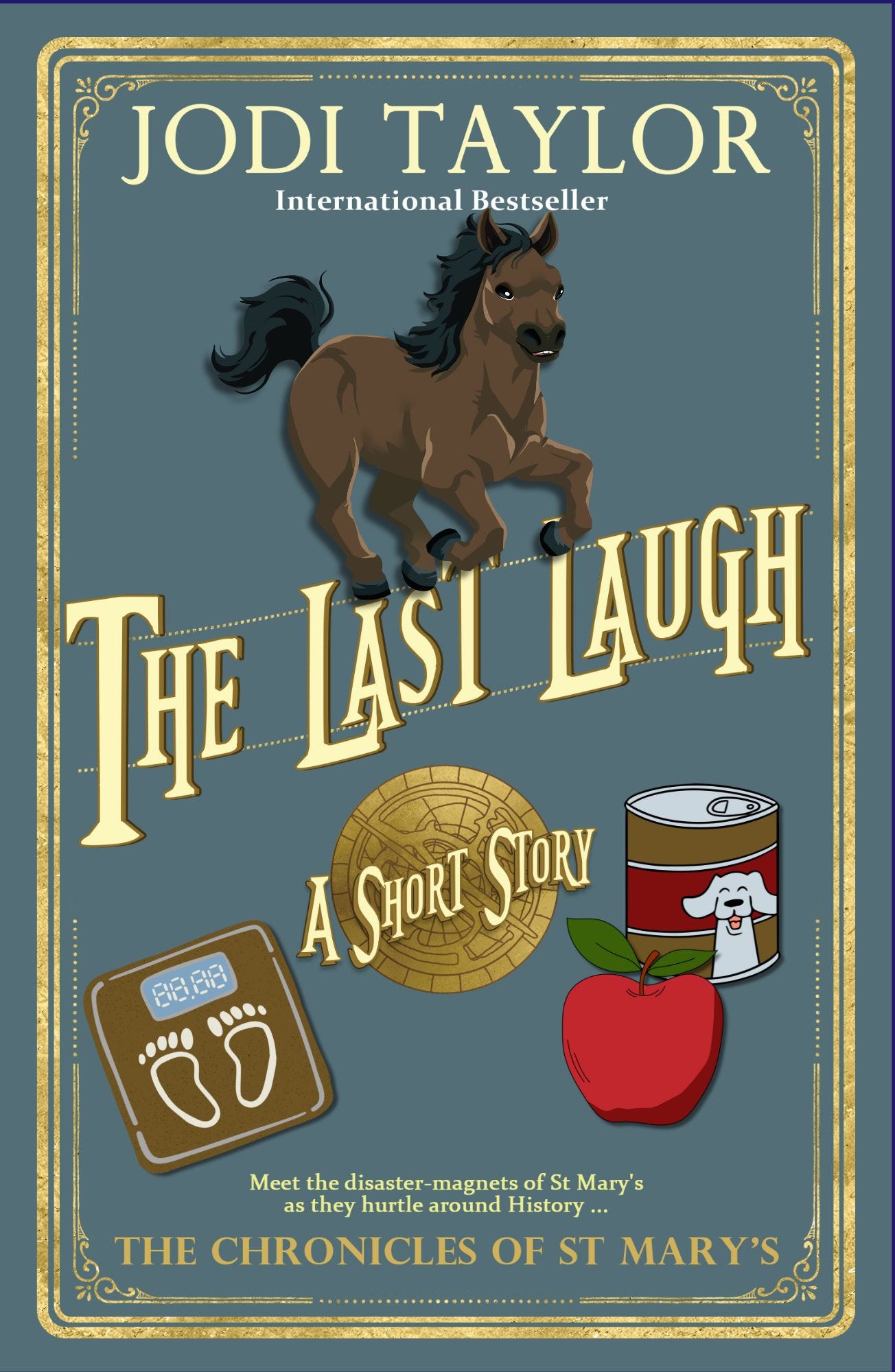

The Last Laugh - a free Jodi Taylor short story

Max is due for her annual check-up - what could possibly go wrong?

I have to say I genuinely have no idea why people are always banging on about my weight. For everyone’s information I can still fit into the socks I bought ten years ago. Although it’s fair to say I’m the only person who finds this feat even remotely impressive.

However, with my annual physical coming up next Tuesday I decided four days was long enough to undo the ravages caused by twelve months of intensive sausages, alcohol, chocolate, nowhere near enough physical exercise and a very dodgy work/life balance. Accordingly, I thought a quick run around the lake would be a good start.

Obviously, a quick run turned into a brisk walk which turned into a slow stroll which terminated in a visit to the paddock to stand in the warm sunshine, leaning on the top rail to watch the horses doze in the sunshine, all of them far too intelligent to indulge in anything as daft as annual physical checkups.

Whatever their work/life balance was, it obviously suited them perfectly. They stood under the trees, half asleep, ears drooping, tails swishing in the heat and definitely not worrying about how to shed ten pounds in four days. Actually, three and a half days now. Three pounds per day. Too much to achieve by my usual practice of going to the loo, wearing fewer clothes, and only standing on one leg. At a pinch I suppose, I could chop all my hair off but then I’d only be swapping one problem for another. Cutting my hair would inevitably lead to Mrs Partridge materialising at my elbow – I’ve no idea where she comes from – an alternate universe, perhaps – and uttering those fatal words, ‘Dr Bairstow would like a word, Dr Maxwell.’

No. My only recourse was to sabotage the scales. Somehow. I could do something with magnets, perhaps. Obviously, I’d have to be subtle about it. No one would ever believe I’d achieved optimum weight overnight – not after all these years – but I could rig them to read, say, just two pounds over my upper limit. That would be believable. Dr Salt would be so pleased I’d complied with her strict instructions and lost a whole eight pounds that she wouldn’t investigate any further.

I sighed. I was kidding myself. This was Dr Salt. There would be a full forensic examination, culminating in an extensive interrogation concerning my bowel movements and the lack thereof. It was only July. It was months before the next one was due. Trust me, the summer and winter solstices are big events in my life.

No, I was kidding myself. The only way I was going to get through next Tuesday was either to steal the scales or amputate something. Or possibly burn the building down. Hm …

I was plotting Ways and Means when my old enemy strolled up, planted himself in front of me, laid back his ears, and eyed me balefully.

‘Hey, Turk, you old bugger. I’m afraid I don’t have anything for you,’ I said, patting my pockets to show I didn’t have anything for him.

I half expected him to curl his lip at me and push off – that was just about the sum of our relationship – but he didn’t. He rested his head on the top rail beside me, half-closed his eyes and let his bottom lip dangle, exposing unspeakable but sadly fully-functional teeth.

I was instantly suspicious. This was not typical Turk behaviour. And I should know. He and I had a long-standing … relationship hardly seems the right word. He’d been at St Mary’s even longer than me. I could still remember the day we’d met. I’d been a trainee at the time which meant that my permanent physical state was hunger and my mental state oscillated wildly between terror, excitement and exhaustion. All historians have to be able to ride and female historians have to ride side saddle so I and my partner, Davey Sussman had been dispatched to the stables to get some hours logged.

Two horses stood ready and waiting to be saddled. It wasn’t really much of a choice. The horse on the left – Horse A, if you like – was a sweet-looking chestnut mare with gentle eyes, a neat little star peeping out from under her forelock, and a general air of affection and benevolence.

Horse B, on the other hand, was enormous, dirty brown, bony, possessed a malevolent expression, and had feet the size of Rutland.

Obviously my first choice was Horse A – an absolute sweetie. We were obviously made for each other. Fatally, I paused for one moment, lost in a pleasant daydream where I, wearing a stunning green riding habit with one of those floaty-scarf hats, cantered gracefully hither and yon, the epitome of perfect side-saddleness and earning the admiration and envy of all. And prizes at the county show as well.

I say fatally, because taking advantage of my very temporary inattention, Davey Susman shouldered me out of the way, saying, ‘Don’t fancy yours much, Max. Well, hello, Beautiful.’

Horse A practically leapt into his arms. It was love at first sight.

‘Oh good, you’ve sorted yourselves out,’ said Mr Strong, appearing from inside the stables. ‘Interesting choice, Miss Maxwell.’

Sussman sniggered and he and Horse A disappeared into the sunset and eternal happiness, leaving me with the unholy offspring of a toast rack and a mildewed carpet.

‘His name’s Turk,’ said Mr Strong, disappearing back into the stables. ‘Sometimes he responds to bribery. Mostly he doesn’t.’

I tried. I swear I tried. I spoke gently into his ear and he flung up his head and made my nose bleed. I stroked his neck and he trod heavily on my foot. Once, when brushing him down I spent twenty minutes pinned against a wall until an hysterical Grant and Nagley found me and pulled him off. Nothing worked. Every time I took him out, I gave him one apple, reserving the second against a safe return. He never got it. Every ride ended with me doing the walk of shame back to St Mary’s, trying not to trip over my muddy riding habit, cursing stupid Anne of Bohemia, stupid wife of stupid Richard II, who had introduced the stupid side-saddle style to England in the first place and whom I held personally responsible for my current difficulties. The problem was that a side-saddle session constituted part of the final exams and I began to worry.

Typically, it was Sussman, who, having lumbered me with this equine thug in the first place, came up with a sort of solution. He watched the apple trick one day and was waiting for me when I later limped back into the stable yard. On foot, obviously, with Turk following on a mocking couple of yards behind me. I expected caustic comments because he had a sharp tongue but he simply raised an eyebrow and disappeared. He reappeared a few minutes later and said, ‘Bring him out again.’

I was just about to unsaddle the evil, stubborn, bloody-minded bastard formerly known as Turk and was thinking longingly of a hot bath, but he said, ‘No, come on. Bring him out into the paddock.’

So I did.

‘Now,’ he said, instead of an apple, try this,’ and he set a tin of dog food on the top rail. The three of us regarded it silently.

Eventually, I said. ‘Um … What’s that?’

‘The Davey Sussman Dog Food of Doom.’

‘The what?’

He stepped up to Turk and grabbed the bridle.

‘Now listen to me, you shaggy brown shithead,’ he said. ‘No more Mrs Nice Guy for you. See this?’

He picked up the tin and waved it in front of Turk. ‘This is an ex-horse.’

‘Davey!’ I said, half-laughing, half-horrified.

‘And you, my bony friend, are only two steps away from being potential dog food. This is a nice lady. Treat her right and you end your days in peace and plenty. Treat her wrong … and you end your days in a tin.’

I sometimes think the greatest time travelling device of all is the mind. At that moment I could smell the hay and horse shit. I could feel the crisp autumn day. I could hear his voice clearly. ‘Treat her right …’ If only he’d listened to his own advice, then maybe his own end wouldn’t have been so bad …

But back to Turk. It wasn’t that simple, of course. Yes, there were good days with him but they were still outnumbered by the bad ones. He would sweep me out of the saddle under low hanging branches. He would deliberately misjudge the width of an open gate and smack my knee against the gate post. At great speed usually. He made numerous attempts to roll on me. He regularly and painfully stood on my feet. Normally I’d pummel him and shove and shove until he moved but one day he managed to stand on both my feet and I was helpless and had to shout for help. It seemed an age before some scruffy security guard named Markham had turned up in answer to my shrieks Fortunately – for me – Markham appeared to be the one person Turk regarded with even more hostility than me. I was abandoned without a second thought as he chased Markham across the paddock to crush him against the fence and eat him.

Crippled though I was. I heroically hobbled after them and after a lot of shouting, shoving, cursing, crying – that would be me and Markham doing the crying – and ferocious snorting – that would be Turk – I was finally able to free Markham and we scrambled over the fence with more haste than dignity. Markham had his arse nipped, just to speed him on his way

And that was our relationship – mine and Turk’s – for the next God knows how many years, so you can understand my caution when he voluntarily came to stand beside me, showing all the signs of a normal horse just wanting his ears fondled in the sun.

Somewhat apprehensively, I stroked his dusty neck – and retained full use of my arm. I rubbed his forehead and he closed his eyes and grunted in pleasure. I stroked his nose and didn’t lose a single finger. Emboldened – or possibly lulled – I climbed over the fence to stand beside him. I tidied his mane and smoothed his forelock. The sort of thing you can do to normal horses and live. He closed his eyes and sighed.

‘Hey there,’ I said. ‘You’re not such a bad old bugger, after all, are you?’

He rubbed his head against me but gently, not in any sort of disembowelling context, and made a strange sound indicative of equine contentment. Or so I thought. For a few seconds, we stood in peaceful harmony. I laid my cheek against his neck. ‘Who’s a good old boy, then?’

The next moment his legs buckled and he went down like a tonne of horse-smelling bricks – bringing me down with him – and lay quite still.

I lay on my back with a crushing weight across both legs and wondering what on earth had just happened. Turk. Turk had collapsed. Oh God, I knew he was old and now he’d had some sort of heart attack. His head and neck lay across my mid-section. I was trapped underneath a dead horse. The old bugger had died and, in true Turk style, had taken me with him.

Does anyone have any idea how heavy a horse can be? When you’re partially buried underneath one? I was slowly being crushed to death.

But no. Hold on. He was still alive. I could hear his heavy breathing. If I lifted my head and squinted, I could see the pink of his distended nostrils as he struggled to breathe. See his eyes, showing even more white than usual. He must be terrified. He wouldn’t understand what was happening to him. I don’t know if animals have any concept of death. Or had he, in some vague horsey way, been aware of his approaching end? Was that why he had sought out human company? So he wouldn’t be alone as his soul flitted away to horse heaven? I’ve always wanted to believe that somewhere there’s a special place for horses. Somewhere for them to go when this world has finished kicking them, beating them, starving them. Some reward for their patience and their loyalty. For always doing their best.

I imagined him young and strong, galloping free, through the woods, up on to the moors, the wind blowing through his mane, full of life and strength, faster and faster, never stopping, leaving this world behind, out among the stars, never pausing, never slowing, his eyes fixed on something I would never see.

I managed to wiggle around and pat some part of him. ‘It’s all right. Turk. It’s OK. It’s fine. Everything’s absolutely fine.’

From far off I heard a shout. Had someone seen us?

I waved my arm, shouting, ‘Over here. Help. Hurry.’

Turk made that soft, sad sound again. Reaching out, I stroked his neck. ‘I’m going to miss you. Poor old Turk. My favourite old boy.’

For a few seconds there was complete silence and then, almost as if he’d planned the entire episode and been waiting for that very moment, he lifted his head, heaved himself to his feet – without standing on me even once – and strolled away, his tail swishing in disdain. Not even a backward glance.

I lay for a moment just enjoying the whole blood returning to my legs thing when Markham skidded to a halt beside me. ‘Max, are you all right? Can you move?’

I experimented with bits of my nether regions. ‘I think so.’

‘Don’t tell me he got you too.’

‘What?’

‘He’s been doing this all week apparently. ‘So far, he’s got Mr Strong, Polly Perkins, Bashford – twice – and Glass.’

‘My bones are all caved in,’ I said, seeking sympathy.

Unsuccessfully. ‘No, they’re not. He’s actually quite gentle you know.’

I blinked up at him. ‘What?’

‘It’s his new game. He keels over and lies there until his victim tells him they love him really – or in Polly’s case, cries all over him – and then he gets up and walks away. Although you are the only person he’s actually taken down with him but it’s quite a neat trick, don’t you think? Up you get now – you can’t lie in the dirt all afternoon. Leon won’t like it.’

Markham helped me up. And he was right – I was crumpled and dusty but completely uninjured. Apart from my dignity, of course. I looked across the paddock at Turk, now quietly grazing with all the other horses. Horses don’t high five – at least I assume they don’t – but I swear I could hear them sniggering from all the way over here. Turk himself lifted his head, staring at me with the smug expression of a horse having the last laugh.

‘You big, bony, brown bastard,’ I shouted. Adding, ‘Not you,’ as a startled Markham stepped back a pace.

I stared at him and narrowed my eyes. ‘You’re a cat owner.’

‘Yes,’ he said, cautiously.

‘Got any pet food on you?’

‘Oddly – no.’

‘Why the hell not?’

‘I expect it’s in my other uniform. Come on – I think we should get you checked out.’

‘I’m fine,’ I said wearily.

‘No,’ he said, meaningfully. ‘I don’t think you are.’

‘Yes, I am.’

‘No,’ he said, as if to an idiot child. ‘You’re not.’

I stopped. ‘No. You’re quite right. I’m not.’

‘Lean on me,’ he said, concern written all across his face. ‘I can only pray we get you to Sick Bay on time.’

‘Well,’ said Dr Salt, peering at the screen. ‘I can’t see anything wrong but it’s you, Maxwell, so I’m not prepared to commit myself. It’s no joke having a horse fall on you.’

‘No,’ I said, weakly, sagging artistically in my seat. ‘I’ll be fine. Absolutely fine. And I’m due in Smyrna next week.’ Adding hopefully, ‘Perhaps you could give me something to keep me going. Like the Time Police do.’

She scowled. ‘And find myself accounting to Dr Bairstow for a drug-crazed historian causing chaos in Smyrna – forget it. Today and tomorrow off. Light duties for forty-eight hours after that. Annual checkup postponed twenty-eight days. Which is a shame. I was looking forward to your feeble attempts to convince me you’d lost ten pounds in three and a half days. Now push off and stop cluttering up my nice Sick Bay.’

Love it! :) I clearly remember the joy of being casually scraped off on a low branch by a sneering horse. :)

I always need a trip to St Mary's!

Thank you Jodi.