Christmas Day 1642: The Birth of Isaac Newton

This Week In History: A Life That Changed the Laws of Nature

On 25th December 1642, in the quiet Lincolnshire countryside, Isaac Newton was born in the hamlet of Woolsthorpe near Colsterworth. England was then in the grip of civil war, and few could have imagined that this frail infant, born prematurely and not expected to survive, would come to transform humanity’s understanding of nature more profoundly than almost any other individual in history.

Newton’s early life was marked by instability and solitude. His father had died before he was born, and his mother remarried when Newton was still a child, leaving him in the care of relatives. This sense of isolation shaped a temperament that was inward-looking, fiercely independent and intensely focused. At the King’s School in Grantham, Newton showed early signs of mechanical ingenuity, constructing sundials and small working models. These interests were not yet signs of genius, but they revealed a mind drawn to order, measurement and the hidden principles governing the physical world.

In 1661, Newton entered Trinity College at the University of Cambridge. There, he encountered the new mathematical and scientific ideas circulating in Europe, including the work of Descartes and Galileo. Cambridge at the time still taught largely Aristotelian natural philosophy, but Newton pursued a private programme of intense study, absorbing and extending the most advanced ideas of his age.

The years 1665 and 1666 were decisive. The Great Plague forced Cambridge to close, and Newton returned to Woolsthorpe. In this period of enforced isolation, often described as his miraculous years, he laid the foundations of several disciplines. He developed the basic ideas of calculus, formulated the laws of motion, and began to think seriously about universal gravitation. The famous story of the falling apple belongs to this time, not as a literal moment of discovery, but as a vivid illustration of his insight that the same force governing falling objects on Earth might also govern the motion of the Moon and planets.

Newton’s mathematical achievements alone would secure his place in history. His development of calculus, which he called the method of fluxions, provided a powerful new language for describing change and motion. Although a priority dispute with Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz later clouded its reception, calculus became indispensable to science and engineering.

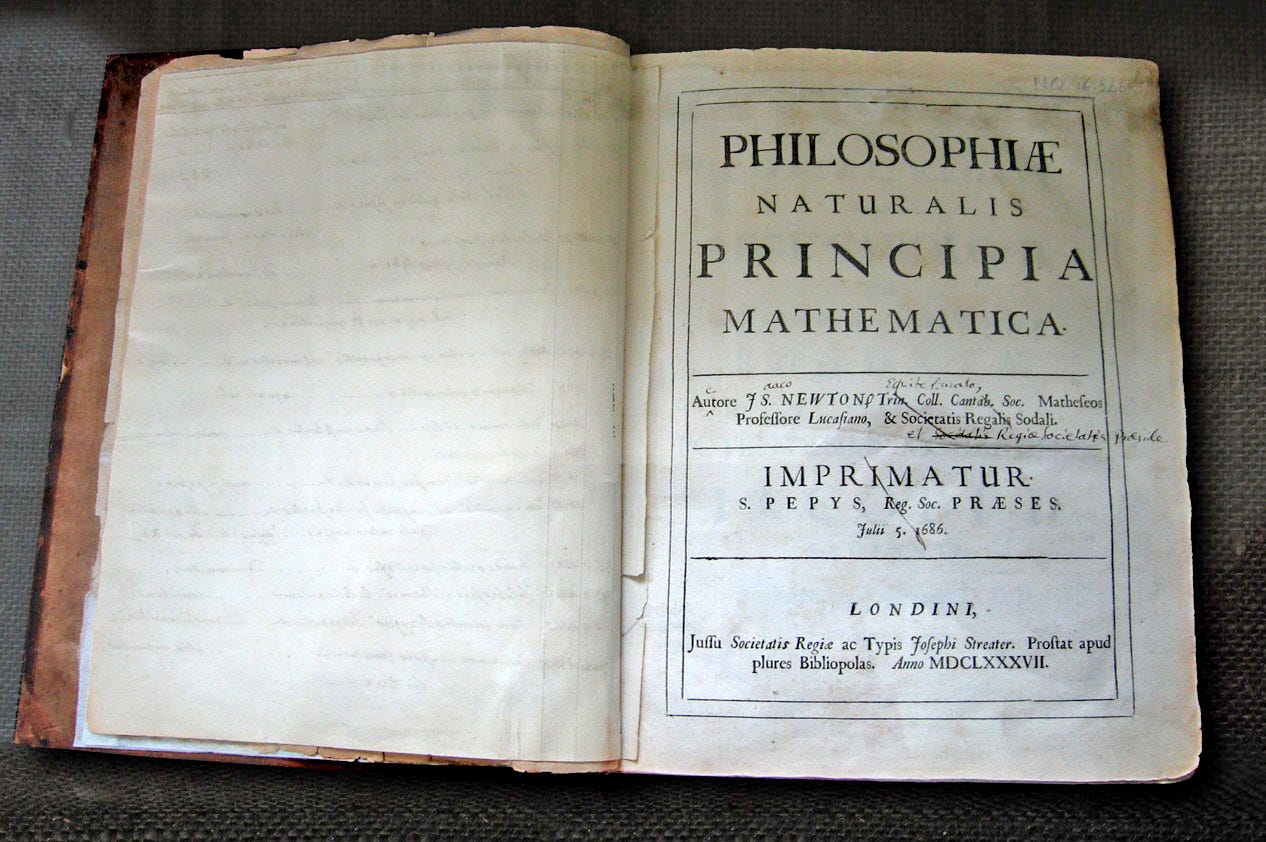

In natural philosophy, Newton’s most significant work was Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica, published in 1687. In this demanding and austere book, he set out three laws of motion and the law of universal gravitation. Together, these principles explained phenomena ranging from the fall of an apple to the motion of comets with unprecedented precision. The Principia unified the heavens and the Earth within a single mathematical framework, overturning centuries of philosophical division.

Newton also transformed the study of light and colour. Through careful experiments with prisms, he demonstrated that white light is not pure but composed of a spectrum of colours. This contradicted long-held assumptions and established optics as a quantitative science. His construction of the first practical reflecting telescope further demonstrated his experimental skill and ingenuity, and earned him early recognition within the Royal Society.

Despite his preference for solitude, Newton played a significant role in public life. He served as Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at Cambridge, later becoming Warden and then Master of the Royal Mint, where he oversaw a major reform of English coinage. He was elected President of the Royal Society and knighted in 1705, becoming Sir Isaac Newton.

In his later years, Newton devoted increasing attention to theology and alchemy, fields that modern readers sometimes find surprising. Yet these pursuits reflected his lifelong conviction that nature, history and scripture formed a coherent whole, governed by divine order.

When Newton died in 1727, he was buried in Westminster Abbey, an honour rarely accorded to a scientist. His influence extended far beyond his lifetime. For more than two centuries, Newtonian mechanics provided the framework within which science understood the physical universe. Even after the advent of relativity and quantum theory, his laws remain indispensable approximations in countless practical contexts.

I hope you have enjoyed this foray into history. Please subscribe to read more articles like this.

CLICK HERE to read more History and Happenings articles.

Have you discovered The Official Reading Companion and History Briefings for The Chronicles of St Mary’s series by Jodi Taylor?

If you’ve ever found yourself wondering who did what, when, and where in Jodi Taylor’s brilliant Chronicles of St Mary’s series — this is the companion guide you’ve been waiting for.

This guide is a must-have for both dedicated fans and curious newcomers. It contains synopses of every book and short story, detailed floor plans of St Mary’s Institute for Historical Research, History Briefings, chronological jump lists, character information, and more.

Whether you’re brushing up on the timeline or want to immerse yourself further in the chaos and charm of St Mary’s, this guide is your ultimate companion.

CLICK HERE to learn more.